Week 14 - Dual Use Technologies - Cryptography

August 2024 (2724 Words, 16 Minutes)

I’ve planned a three-part series on how American industrial policy has affected technology development by highlighting the history of a few dual-use technologies. Today, we’ll look at past attempts by the American Government to govern the flow of cryptography research. In the next installment, I’ll look at the government’s involvement in AI Research and chip fabrication.

Cryptography

For younger hackers, it’s surprising to learn that cryptography was once a heavily regulated field. We’re used to running pip install pycryptodome and having free reign of state-of-the-art open-source cryptography tools. The open-source nature of this software provides a net benefit from the security that encryption provides to our increasingly networked world.

However, portions of the US Government have held differing viewpoints over the years. Cryptography was once solely the responsibility of military signals intelligence personnel until about the middle of the Cold War. Think Commander Deniston (Charles Dance’s character) in The Imitation Game. As such, cryptography was defined as a military asset by the Department of State’s International Traffic in Arms Regulation (ITAR). This is the same regulation set that governs the export of military assets like ammunition, firearms, spacecraft, and nuclear weapons research. The fear of the era was that sharing cryptographic techniques would jeopardize national security by exposing Signals Intelligence (SIGINT) sources to adversaries.

SIGINT is one of the five main intelligence sources and deals with electronic communications. Intercepting these signals and turning them into actionable intelligence has been the National Security Agency’s primary responsibility since its foundation in 1951. In those days, the NSA busied themselves with intercepting analog phone calls and radio communications. As analog gave way to digital, the NSA has worked hard to keep ahead of the curve. In the modern era, they conduct honest-to-god cyberwarfare, with the most famous publicly known operation being Stuxnet, a malware operation discovered in 2010 that crippled Iranian Uranium enrichment efforts for at least half a decade. For the unquestioningly loyal the NSA represents American-bred high technology forwarding democracy abroad and protecting our digital assets at home. For the private, disillusioned, paranoid, or outspoken, the NSA is the most advanced surveillance network in the world that has easily turned on Americans labelled troublemakers by the Government.

But what is cryptography?

Cryptography is the mathematical science of transmitting data between two trusted points over an untrusted medium in a way that the data cannot be deciphered if intercepted. You may remember the push to visit websites that only start with https:// and steer clear from http:// sites that began in the early 2000s. This is because the s in https:// means the connection is encrypted, preventing a “man-in-the-middle” attack from altering or intercepting sensitive data.

In a typical symmetric cryptosystem, you have five pieces of information you care about:

- Plaintext: The information you want to hide.

- Key: The piece of information used to both encrypt and decrypt the plaintext.

- Ciphertext: Encrypted information that should be unintelligible to an outside observer.

- Encryption function: Mathematical process that takes the plaintext and the key to produce the ciphertext.

- Decryption function: Mathematical process that takes the ciphertext and the key to produce the plaintext.

Notice that you use the same key to both encrypt and decrypt the data, hence the adjective “symmetric” in symmetric cryptography. The key is shared over a secure channel between the two hosts. This ensures the confidentiality of the encrypted data. Some of the modern algorithms in this group are AES, DES, and Blowfish. This scheme commonly used when you want to encrypt data while it remains in a file or a database when it’s not being actively used.

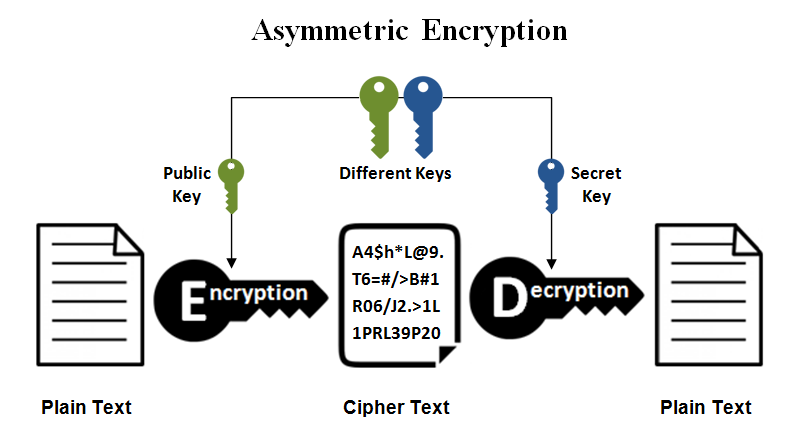

A different paradigm exists called asymmetric cryptography, which uses a combination of public and private keys to both ensure confidentiality and non-repudiation, a fancy word for provable authorship of data. This is useful when validating the source of data or software. If a piece of data can be decrypted with a public key, then we know that it was encrypted with the private key.

This architecture is more complicated to set up, but the benefits of non-repudiation often outweigh the upfront costs. This include the EC25519 and RSA algorithms.

Cryptography and the US Government’s Failings

The national security implications of implementing cryptography become apparent if the medium that the data is being transmitted over, be it a fiber-optic hard line, DSL link, or electromagnetic waves through the open air, is compromised or intercepted. In the days of ARPANET, when four universities exchanged research data over phone lines, the stakes of the data being intercepted and tampered with were low. In the seventies, however, digital networked systems increased in complexity and capability and became a cornerstone in the banking and defense sectors of the American economy. These two sectors require security as a cornerstone of their operations. In the modern landscape, those two sectors are the biggest employers of top-notch cybersecurity talent. This required the introduction of encryption into civilian digital infrastructure to protect financial assets and classified information. In 1977, NIST ratified the Data Encryption Standard (DES) algorithm developed by IBM as a requirement of the Federal Information Processing Standards (FIPS). This required any contractors handling sensitive government data must encrypt it using the DES algorithm. DES is a symmetric encryption method that can take 64-bit message blocks and encrypt them with a 56-bit key. In 1976, before the ratification, Researcher Paul Baran theorized that DES would take about 20 million dollars to break with the hardware of the time. There are only $2^{56}$ or 72 quadrillion possible keys due to the key length being 56 bits. That sounds like a lot unless you work in tech, then you can likely intuit that this is a painfully small amount of possible keys to decrypt data that could have serious national security implications. In 1998, the Electronic Frontier Foundation would demonstrate that it was possible to break the encryption for about 250,000 dollars with mostly off-the-shelf parts in about 3 days. Projecting that rate of improvement to today, it would now take something like a grand of hardware to execute the same attack. Well within the cost of a mid-range laptop.

Deep Crack, the custom-built machine to crack DES by the EFF in 1998

Deep Crack, the custom-built machine to crack DES by the EFF in 1998

Before cryptography had fully embedded itself into the public sector, the Department of Defense had to sign off on any export of cryptography. This means that any research papers, source code, and compiled code would require approval by the Department of Defense before publication. The American Government legally censored cryptographic research, stifling the development of secure methods of communication for Americans and the rest of the world. That previous sentence likely made you question the competence of the American policymaker. You may feel this way because you understand Kerckhoff’s principle, even if you’re not a trained cryptographer.

Kerckhoff’s principle is a core design philosophy of modern cryptographic systems. The principle states that a cryptosystem should be perfectly secure even if everything except the secret key is known to an attacker. This means that an attacker cannot decrypt a message even if they know the version of the specific cryptographic implementation, destination, source, message length, or any other characteristic of the message. In the modern internet environment, including the connection you are reading this article on, sometimes more than a dozen separate legitimate organizations intercept the data that makes up this website. No one, not even an attacker with full access to one of the routers handling this connection, will be able to read the plaintext contents of the encrypted data without possessing the secret if an encryption scheme was implemented correctly.

There are some caveats with the phrase “perfectly secure” that will make mathematicians who attended week 2 of a graduate-level cryptography class bristle at my cavalier usage of it. To a layman, however, the point gets across.

Kerckhoff’s principle is a vocab word that every Mathematics, Information Technology, and Cybersecurity student has had to memorize for a multiple-choice question on a midterm (or in my case, a crossword answer). The principle is intuitive. In a scenario where you are transmitting sensitive information over a medium that can be intercepted, it is only a matter of time before an attacker reverse-engineers the encryption scheme. A cryptosystem that is designed to be secure by having many complicated steps in the encryption and decryption processes that are unknown to an attacker is objectively worse than a cryptosystem that relies on public and peer-reviewed algorithms and implementations. This makes sense for the same reason that open source is so powerful. Anyone with the proper training can discover vulnerabilities and make them public. Good-faith researchers can point out flaws in an implementation, preventing them from being used by cybercriminals and nation-states alike. Improving the security of an algorithm and thus the entire internet ecosystem.

With this understanding, it is no surprise that the Government has not sought to restrict the export of cryptography to the international community in nearly three decades. If the Government could only utilize research from American cryptographers who can obtain clearance, want to live in Washington DC, and are willing to be underpaid for their skills instead of raking it in as a high-frequency trader on Wall Street, the American Military would fall behind the rest of the world, a state of affairs that is entirely anathema to what it means to be an American. The last time the US Government tried to exercise these export controls on academic cryptography research resulted in Bernstein v. Department of Justice, 1998. This landmark case set the precedent that source code is protected as freedom of speech under the First Amendment.

Bernstein v. United States and Code as Speech

In 1990, Daniel J. Bernstein, an American Berkeley student, developed an experimental algorithm called Snuffle. He attempted to comply with export controls to distribute his work to Sci.crypt, a cryptography-centric forum. He was denied an export license despite his insistence that there was no military utility to the work. Bernstein appealed his initial request but was ignored for fifteen months despite regulations requiring a government response to such requests within thirty days. In 1995, Bernstein and the Electronic Frontier Foundation filed a lawsuit in the North District of California against the US Government, alleging export controls on source code and research were unconstitutional.

Source code can be viewed as a different from of a plain English representation of an algorithm. Using a program called a compiler to turn source code into executable code, source code can be subjected to the same academic rigor that a typical mathematical proof is through automated testing. An excerpt from the argument presented by Bernstein’s lawyers highlights how keeping in line with the First Amendment requires treating source code with the same freedom of speech protections as a plain-English algorithm:

As noted earlier, the chief task for cryptographers is the development of secure methods of encryption. While the articulation of such a system in layman’s English or in general mathematical terms may be useful, the devil is, at least for cryptographers, often in the algorithmic details. By utilizing source code, a cryptographer can express algorithmic ideas with precision and methodological rigor that is otherwise difficult to achieve. This has the added benefit of facilitating peer review – by compiling the source code, a cryptographer can create a working model subject to rigorous security tests. The need for precisely articulated hypotheses and formal empirical testing, of course, is not unique to the science of cryptography; it appears, however, that in this field, source code is the preferred means to these ends.

Footnote 14 of that document points out that the subject of this article, Bernstein’s Snuffle algorithm, isn’t even a complete cryptographic product. It’s just an educational proof of concept. The plaintiffs argue that the Government mistakenly separates source code as unable to constitute a meaningful expression, as opposed to something like a blueprint or a manual, because of the presence of “direct functionality.” They argue that if Adam Smith wrote the Wealth of Nations with equations or graphs, it would potentially be subject to prepublication review to show the absurdity of regulating academic discourse based on the possibility for the findings to be applicable in the real world. The National Security Agency has shown a disregard for considering cryptographic source code as expression, stripping it of First Amendment protections. The article cites a statement made by the NSA:

Whatever ideas may be reflected in the software, or the intent of the exporter to convey ideas, the NSA recommends that encryption software be controlled for export solely on the basis of what it does.

There have been instances where First-Amendment protections can be legally trampled in the face of a plausible and immediate national security threat. The argument cites the famous United States v. Progressive Inc. where the Department of Energy sought an injunction against The Progressive, an American magazine, for attempting to publish an article on the technical details of the then-classified Hydrogen Bomb. According to the Free Speech Center, the injunction was ultimately unsuccessful in its goal as at least seven publications released similar articles. Skimming through the article today, it’s interesting how the information that drew the American Government’s ire 50 years ago is now common knowledge for anyone with a cursory interest in nuclear energy, or enjoy videos on Kerbal Space Program. Despite this failure to contain delicate information, the case is cited today when the American Government seeks to preserve national security at the expense of free journalism. If Bernstein was a cleared ex-NSA cryptographer known to be sympathetic to the Soviet Union publishing classified algorithms to a European journal, a credible national security threat is present, and an export license could easily be denied to prevent the dissemination of state secrets. However, Bernstein was a researcher at a top-of-the-line public research university developing his own encryption algorithm. His work presented no credible and immediate national security threat, and thus restriction of his work under ITAR was deemed unconstitutional by Judge Patel.

Cryptography and the US Government’s Successes

Bernstein v. United States was decided in 1996 with attempts made to reverse the decision going all the way to 2003. In the intervening 28 years, there have been no public attempts by the US government to regulate academic research into cryptography and the development of new algorithms and attacks. In fact, the CHIPS and Science act provides funding for public research into future-proofing our communications systems with quantum cryptography. This shift has shown that the American policymaker is actually capable of making a forward-thinking decision, much to many Americans’ surprise. When/if/when we can get quantum computers working, these expensive gizmos have the capability of revolutionizing the world of cryptography, making computationally impossible attacks with classical computers not only feasible, but trivial. If you’re a remarkably short-sighted national security professional, this investment into public research into quantum cryptography could strip the ability of the American intelligence community to create actionable intelligence in the future. However, any intelligence analyst will tell you that our adversaries are capable of developing quantum hardware and are not likely to share the advancements with the rest of the world. The difference between the United States and our four major adversaries in China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea is that we choose to govern as a liberal democracy. Our policymakers are incentivized to recognize when the short-term gains of increased visibility into the world’s communications at the expense of long-term security for both our people and our nation is a tradeoff that should not be made. It seems we have exported this habit to other nations. Today, the cryptography community is full of hackers, academics, government researchers, and hobbyists from every corner of the globe, with American universities training the top minds in the field.

Resources

Here’s a list of my favorite resources that provide a good introduction to Cryptography without a formal mathematics background.

- Cryptohack: A website that teaches advanced cryptography from first principles. Go from XORing messages to implementing elliptical curve cryptography and beyond by hand.

- Cryptohack Discord: The discord community for the Cryptohack website. Join hobbyists, hackers, and researchers alike unified in their love for breaking into things.

- cryptopals: Another website providing CTF-like challenges for cryptography.

- Math 290 textbook: Helps with writing proofs

- A Graduate Course in Applied Cryptography: Free textbook from Stanford

- Mathematical Proofs: A Transition to Advanced Mathematics: Introduction to thinking and writing proofs. If you are already have a formal mathematical background, I asked my friend Macen Bird to collate some of advanced resources in the space:

- Fields and Galois Theory

- Algebraic Number Theory

- Practical lattice reductions for CTF challenges

- AES Cryptanalysis for beginners

- Cryptographic key recovery paper

- Elliptic Curves over Finite Field - Used in any elliptic curve algorithm

- A Gentle Tutorial for Lattice-Based Cryptanalysis

- An Introduction to Mathematical Cryptography

- Lightweight Introduction to Lattices

Music from this week

Akhasmak Ah - Nancy Ajram

Ella Baila Sola - Estaban Armado

LA PEOPLE II - Peso Pluma, Tito Double P, Joel De La P